From the Greek “stereo” (“solid”) and opsis (“power of

sight”) stereopsis is perceiving depth, relief, or three-dimensions (stereopsis,

n., 2012). This ability is most commonly due to binocular vision, where the

spacing of two eyes creates separate images of a scene from slightly different

angles, which are then combined into one vision with three-dimensional quality in

the brain.

The application of three-dimensional vision to

two-dimensional images, by using a viewing implement, or a stereoscope, was first described by English physicist Charles

Wheatstone in 1838. He created his stereoscope with prisms and mirrors, and it

was originally used for viewing drawings.

|

| Wheatstone stereoscope. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stereoscope |

Scottish physicist David Brewster improved the stereoscope

in 1849, inventing the “refracting” or “Lenticular” stereoscope, which was

reduced in size and used lenses instead of mirrors. He also invented the double

camera for taking stereoscopic views, which were afterwards mostly produced

with such double-lensed cameras.

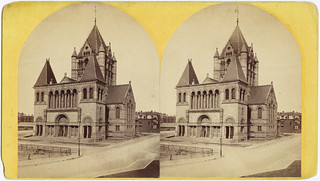

These photographs were produced as stereographs, with two images side by side. Stereographs are a

photographic format, not process, and were produced using multiple technical

processes over time, including the daguerreotype, ambrotype, wet plate glass

positive, mounted salted paper print, albumen prints, and gelatin print

processes (Ritzenthaler & Vogt-O’Connor, 2006, p. 41). The majority of

stereographs, also called stereo views, were mounted on cards.

|

| Folson, A. H. (c.1850-1929). Trinity Church, Boston. Retrieved from http://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/2351548106/in/set-72157604192771132 |

Daguerreotype stereographs were first publically exhibited

in 1851 at the London International Exhibition, and were received enthusiastically

by Queen Victoria and others (history of photography, 2013). Their popularity

grew even more with the simple hand-held version of the stereoscope developed by

Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1861. Holmes’ invention, which was easy to

manufacture, combined with his excited promotion of stereoscopes and

stereographs in The Atlantic, helped

to boost the already popular form in the United States.

|

| Holmes stereoscope. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stereoscope |

Stereographs were extremely popular from 1850

through the 1920s and 1930s (the rise of newsreels), and during this period

millions of stereographs were produced.

Photographers were sent out to photograph the world, and manufacturing the

views was a big business. One of the first firms to produce stereographs was

that of the Langenheim brothers, and later the leading publishers were

Underwood & Underwood and the Keystone Company. Views could be bought

individually, or more often, in large topical groups.

Stereoscopes became a popular instrument for home

entertainment and education (much like radio, and then TV) and had an important

impact on public knowledge and taste. Holmes was correct in his statement

regarding the stereograph that, “Men will hunt all curious, beautiful, grand

objects,” as the market for stereographs was expansive, and diverse (1859).

Images captured local history, grand landscapes, foreign scenes, important

people, architecture, war, disasters, and later on, staged scenes of humor and

the home. Curiosity about the world was a huge force in stereographic

popularity, and travel images as souvenirs, and of places one might never see,

were very popular.

|

| Norman Rockwell painting of a boy viewing Egypt through his stereoscope. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Rockwellboywithstereoscope.png |

The expansion of the business of stereographs and their broad

popularity not only impacted those directly involved, but also had an indirect

impact on other branches of photography and visual theory at the time. Holmes

not only wrote of the curious and beautiful objects available in stereographs,

but also noted that “form is [now] cheap and transportable” (1859). Whether intentional or not, this idea

was felt by those who saw in the stereograph (especially by the end of the

century when stereographic photography had become quite uniform,) the

cheapening of photography into popular commercialism. While these images

would inform the conventions of publicity and advertisement photography in the

future, they also pushed some photographers into “High Art” in response to

“stereoscopic trash” (Jeffrey, 1981, p. 38).

Despite these other opinions, and the branching out of new

forms in reaction to stereographs, it should be clear that stereographs hold

great importance for cultural heritage institutions who might seek to collect,

preserve, and offer access to these images. The broad use of stereographs in

everyday residential life during these decades, along with the diversity of

tastes and communities served by different stereograph subjects, has a strong

impact on their usefulness for researchers in a number of fields. Their

cultural currency is obvious in terms of looking at mass media, middleclass

households, education, and the images themselves are rich in visual and

contextual information, covering topographic views, local history, events,

industries and trade, costume, urban and country life, humor, and portraits.

They are also important for researching the history of photography itself,

having been produced by multiple processes (stereoscopic photography,

2013). Preservation of stereographs is accordingly diverse, depending on the

process by which they were made.

Stereographs and stereoscopes form an early node in the

history and technology of three-dimensional viewing. Anyone who played with a

slide-viewer growing up, crossed their eyes at a "Magic Eye, or enjoyed 3D

at the movies has taken part in this history.

References

history of photography. (2013). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/457919/photography

Holmes, O. W. (1859, June). The stereoscope and the

stereograph. The Atlantic, 6. Retrieved

from http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1859/06/the-stereoscope- and-the-stereograph/303361/

Jeffrey, I. (1981). Photography:

A concise history. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ritzenthaler, M. L. & Vogt-O’Connor, D. (2006). Photographs: Archival care and management.

Chicago: Society of American Archivists.

stereopsis, n. (2012). In OED Online. Retrieved from http://0.www.oed.com.library.simmons.edu/view/Entry/189940?redirectedFrom=stereopsis&

Stereoscopic photography. (2013). The New York Public

Library. Retrieved from http://stereo.nypl.org/about/stereoscopy

Wheatstone, C. (1838). Contributions to the physiology of

vision: Part the first. On some remarkable, and hitherto unobserved, phenomena

of binocular vision. Philosophical

Transactions, 128, 371-394. Retrieved from http://www.stereoscopy.com/library/wheatstone-paper1838.html

Additional Resources

The Getty Museum has produced a nice simulation

of stereo viewing.

Boston Public Library Stereographs: http://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/sets/72157604192771132/

Stereograph Cards at LOC: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/stereo/background.html#format

Civil War Stereographs at LOC: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/cwp/stereographs.html

The Center for Civil War Photography, 3-D Anaglyph

Photography Exhibit:

http://www.civilwarphotography.org/3-d-anaglyph-photographs-exhibit

I have no idea why the spacing in this is funky, I can't seem to fix it. Oh well.

ReplyDelete